Opaque Predicates and How to Hunt Them

All content below is for educational purposes only

Today we will see how to deal with opaque predicates from a reverse engineer’s point of view while analyzing obfuscated binaries.

Recently, a new tampering protection solution has emerged on the market so I felt the urge to get my hands dirty in machine code again.

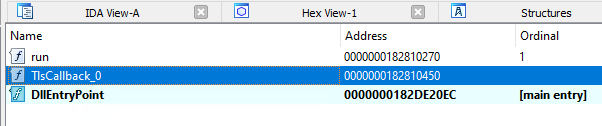

After some quick fingerprinting of a binary obfuscated with this new solution, I figured the first thing to reverse engineer is what is done in the TLS callback (there is only one set).

TLS callbacks are normally used to set up and clear data objects you intend to use on a per thread basis and are local to each thread. However, since this is user-defined code this mechanism is used to execute code before the entry point calling. There are multiple resources online about it, I suggest you to read up on TLS callback abuse if you are not familiar with it.

When reviewing the assembly code inside IDA I noticed some exotic instructions and had a flashback to a previous binary I analyzed years ago (it starts with Over and ends by watch).

The same technique (nothing secret though) is used years after (Obfuscated TLS callback setting up things). Back in the day, I wrote an IDAPython script to handle them as well but it was specific to the binary and the architecture (a lot of things was hardcoded).

This time I decided to do it the proper way by leveraging the power of the MIASM framework, especially its Intermediate Representation and Symbolic Execution modules.

But what are opaque predicates?

Below is the definition of opaque predicate from Wikipedia :

In computer programming, an opaque predicate is a predicate—an expression that evaluates to either “true” or “false”—for which the outcome is known by the programmer a priori, but which, for a variety of reasons, still needs to be evaluated at run time. Opaque predicates have been used as watermarks, as they will be identifiable in a program’s executable. They can also be used to prevent an overzealous optimizer from optimizing away a portion of a program. Another use is in obfuscating the control or dataflow of a program to make reverse engineering harder.

From the definition, we get that an opaque predicate will obfuscate the control flow.

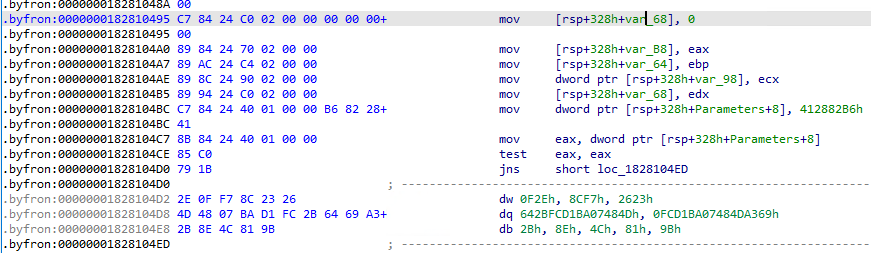

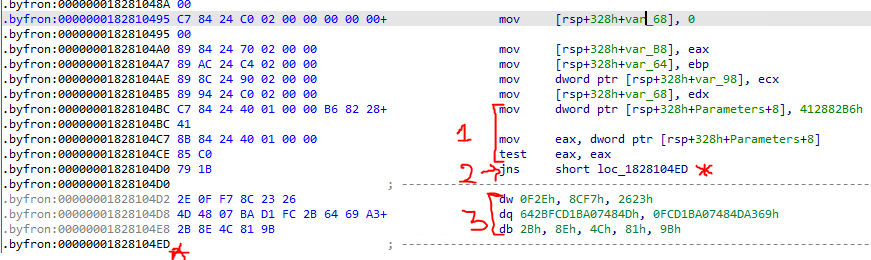

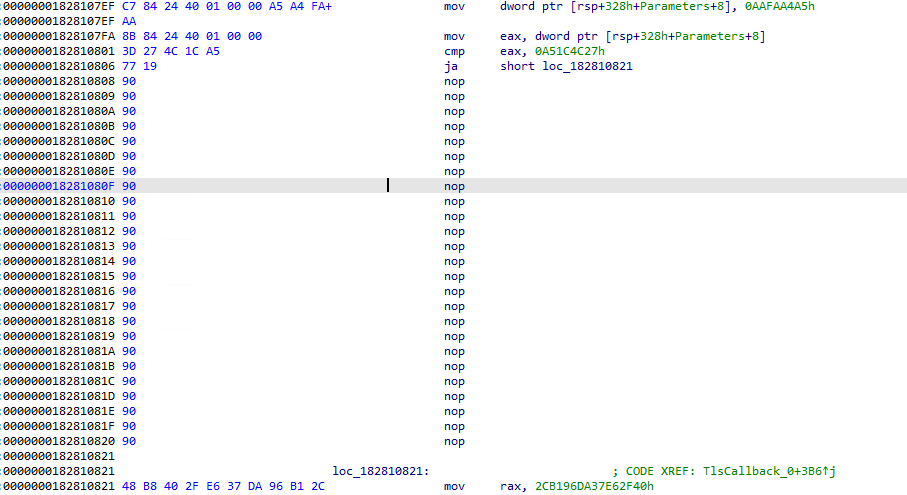

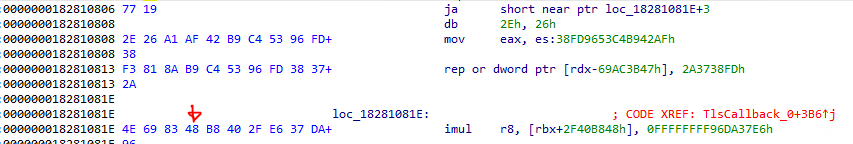

You can see the block computing the opaque predicate, the conditional jump instruction and the junk part, here:

The part labeled 1 is the opaque predicate, the conditional jump is labeled 2 and the junk bytes are labeled with the number 3.

The * labels are the destination location labels (over the junk bytes, the branch is always taken).

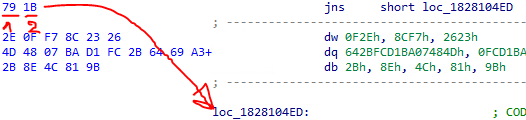

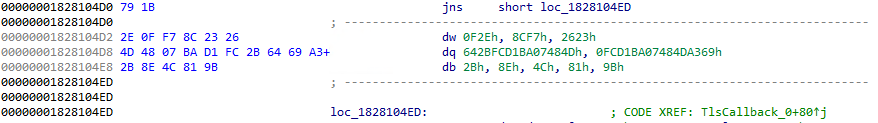

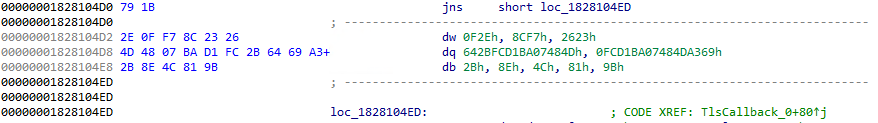

Disassemblers often disassemble a function in a forward looking manner (this is the case with IDA) which means the disassembler will decode an instruction and once the length of the instruction is decoded it will take the next bytes, try to decode them and so on.

The jump (conditional or not) instruction has the following layout:

The part labeled 1 is the instruction opcode and the second (label 2) part is the displacement offset.

This means if the outcome of the condition is fixed at runtime, the branch can always be taken. In the case of a short jump (8-bit operand encoding after the opcode), you can fill the bytes after the instruction with junk bytes (random bytes) up to the jump destination address. One could even generate random but valid instructions to trick the attacker into thinking this is valid code as it would be disassembled correctly.

| Invalid disasm | Almost valid disasm |

|---|---|

|  |

Ok, but why MIASM?

MIASM is a wonderful framework for reverse engineering, it provides numerous tools to ease reverse engineering. It mainly provides an Intermediate Representation (IR) language to automate tasks across architecture but also a Symbolic Execution Engine (SEE) to emulate code blocks and get registers snapshots from the disassembled binary stream.

Combining it with IDAPython allows you to make powerful scripts and/or plugins for IDA.

The plan is to get assembly blocks (in assembly a block starts and ends where branching takes place) just before Jccs and symbolically evaluate them. If the expression of the condition is a constant then we have an opaque predicate.

Fixing the code flow is just a matter of nopping (replacing junk bytes with no operation bytes) the unreachable block and restarting the analysis of the routine.

Let’s go

With all this information we can dig in. I will mostly show code excerpts but you can find the full IDA script here.

Setting up MIASM

Import the following packages :

# Main stuff

#

from miasm.analysis.binary import Container

from miasm.analysis.machine import Machine

from miasm.core.locationdb import LocationDB

from miasm.ir.symbexec import SymbolicExecutionEngine

from miasm.core.bin_stream_ida import bin_stream_ida

# Other stuff

#

from miasm.core.asmblock import AsmBlockBad

from miasm.expression.expression import ExprInt

import miasm.arch.x86.regs as REGSAnd set up the machinery inside the plugin constructor :

def __init__( self ) -> None:

super( op_plugin_t, self ).__init__()

self._unreachable_blocks = []

self._start_ea = None

self._bs = bin_stream_ida()

self._locdb = LocationDB()

self._machine = guess_machine( None )

self._disasm = self._machine.dis_engine( self._bs, loc_db = self._locdb )

self._lifter = self._machine.lifter_model_call( self._disasm.loc_db )

self._symbex = SymbolicExecutionEngine( self._lifter )

self._cur_ircfg = None

self._jcc_map = get_jcc_map()Here is the gameplan:

First thing to do is to open a binary stream to the underlying IDA binary stream using the MIASM bin_stream_ida() helper.

Then we need to create the location database responsible to maintain location relative to the underlying stream and translate them to offsets.

Then we create a machine representation (this is the architecture) with the guess_machine helper (stolen from MIASM examples).

From the binary stream, the machine representation and the location database, we create the dissassembler.

From the machine representation, we can create the IR lifter and from it the Symbolic Execution engine.

The Jcc map is a descriptive map of Jccs to look for and the condition required to take the branch.

The main function is doing 2 things: look for unreachable blocks and patch them.

self._find_unreachable_blocks()

print( f'Found {len( self._unreachable_blocks )} unreachable blocks' )

patched = self._patch_unreachable_blocks()

print( f'Patched {patched} blocks !' )Opaque Predicates and Where to Find Them

To find opaque predicates we take the starting address of the current routine and start disassembling blocks starting from this address to generate a control flow graph.

cfg = self._disas_multiblock_at_addr( self._start_ea )

blocks = list( cfg.blocks )For each disassembled block we check the last instruction of the block listing and check if it is a conditional jump instruction. If we match an instruction we evaluate the condition to check if the branch is taken using the Symbolic Execution engine.

# Run the symbolic execution engine for the block at addr

# and evaluate the resulting expression for the conditionnal register

#

def _eval_register_expr( self, addr, reg ):

self._symbex.run_block_at( self._cur_ircfg, addr, reg )

return self._symbex.eval_exprid( reg )

# Check if the block tied to the conditional jump is an opaque predicate

#

def _check_opaque_predicate( self, block, info ):

self._create_ir_from_block( block )

blk_addr = block.loc_db.get_location_offset( block.loc_key )

cond = info[ 1 ]

regs = info[ 2 ]

exprs = []

for i, ( c, r, v ) in enumerate( regs ):

expr = self._eval_register_expr( blk_addr, r )

if type( expr ) == ExprInt:

value = expr._arg

if ( c == 'eq' and value == v ) or ( c == 'neq' and value != v ):

exprs.append( True )

else:

exprs.append( False )

if len( exprs ) == 0:

return False

is_opaque = False

if cond == 'and':

is_opaque = all( exprs )

elif cond == 'or':

is_opaque = any( exprs )

return is_opaquePatch’em all

Once we collected the unreachable blocks the process of patching them is pretty straightforward.

def _patch_unreachable_blocks( self ):

patched = 0

for index, ( block_start, block_end ) in enumerate( self._unreachable_blocks ):

block_len = block_end - block_start

if block_len > 0xff: # If the displacement is > 0xff ( rel16 or rel32 ) it's probably wrong and need to be resolved manually (just nop the junk)

print( f'Block {index} (start={hex( block_start )}, end={hex( block_end )}, len={block_len}) needs to be reviewed manually' )

else:

print( f'Patching block {index} (start={hex( block_start )}, end={hex( block_end )}, len={block_len})' )

for ea in range ( block_start, block_end ):

idaapi.patch_byte( ea, __1BYTE_NOP__ )

patched += 1

return patchedPatching the now useless mov/jcc blocks is left as an exercise to the reader 😇.

Thanks to babama for proof reading 🦝